AI: Are we in another dot-com bubble?

Foreword

I usually don’t write long thought pieces, but after noticing a growing discourse around this topic, I felt compelled to share my perspectives. What you see here is a product of nearly a month of thinking, reading, and writing. While I don’t expect everyone to agree with my conclusions, I hope this piece offers you insights and sparks your own reflections on the topic.

Hope you enjoy it and please reach out if you want to discuss more!

Introduction

There’s been many bubbles throughout modern human history. The Tulip Mania of the 17th century, the South Sea Bubble, the Railway Mania bubble, the dot-com bubble, the list goes on. Bubbles are so prevalent throughout history because they reflect the juxtaposition of innate human emotions – confidence and doubt, fear and greed, euphoria and panic. However, the prickly thing about bubbles is that while they are glaringly obvious in hindsight, they are notoriously difficult to spot in the present.

But there's never been a lack of those attempting to do so. Lately, the topic of bubbles have resurfaced, with AI being the main culprit. In a recent Bank of America survey featuring 226 money managers, almost half of the respondents believed we were in an AI bubble. Some institutions have already begun to sound the alarm. A recent article published by Goldman Sachs titled: “Gen AI: too much spend, too little benefit?” featured prominent experts questioning the value generated by AI investments. While the article fell short from calling the current AI wave a bubble, the undertone certainly painted quite a pessimistic picture.

Others are more optimistic. For example, in a recent sit-down interview with CNBC, JP Morgan CEO Jamie Dimon stated: “This is not hype. This is real. When we had the internet bubble the first time around … that was hype. This is not hype. It’s real”.

So then, what is the right answer? Are we in a bubble or not?

Because bubbles are so difficult to spot a priori, traditional econometric analysis may not provide the full picture. (If you’re interested in the econometric angle, Ray Dalio presents a really great analysis here)

Another approach is to compare the current AI cycle with the internet/telecom cycle of the late-90s. By understanding the environment that prevailed during that period and the factors driving the dot-com bubble, we can better estimate the risk that we’re in a bubble today.

We’ll analyze this through three questions:

What are the similarities between the current AI cycle and the internet/telecom cycle of the late 90s?

What are the differences?

Based on this comparison, is there a higher or lower likelihood that we are in an AI bubble right now?

Let’s dive in.

First, A Short History of the Internet/Telecom Cycle

To properly compare the AI and internet/telecom cycles, we need to first revisit some history.

While the development of the internet/telecom industry was already underway in the 1980s, it wasn’t until the 1996 Telecommunication Act that opened the floodgate for investments in the private sector. The act sought to reduce regulatory barriers to entry, allowing more competitors in local and long-distance telephone markets, cable television, and other telecommunications services. Between 1996 and 2001, more than $500 billion (~$1 trillion in today’s dollars) was funneled into this sector, supporting companies of all kinds such as network providers, telcos, cable companies, and internet companies. Over this period, more than 300 companies went public, including names such as Netscape (1995), Yahoo (1996), and Amazon (1997).

While there were a few skeptics, the broader market embraced the optimism and drove the equity markets to record levels. From 1996 and 2000, the Nasdaq grew fivefolds from 1,000 to 5,000. IPOs like Yahoo and Amazon saw first-day stock price jumps as high as 1,000%. Any company that marketed itself as an internet company, regardless of whether their business model actually made sense, were bid up by frantic investors trying to get in on the action. As Citigroup CEO Chuck Prince infamously remarked during the 2007-08 financial crisis: “as long as the music’s playing, you’ve got to get up and dance”.

But the music was not to last forever.

In the early 2000s, in an attempt to contain an overheated economy and the “irrational exuberance” in the stock market, Alan Greenspan and the Fed hiked rates six times within 12 months. The correction was immediate – after gaining 400% in four years, the Nasdaq subsequently fell by almost 80% over the next 31 months. Internet darlings like Pets.com vanished almost overnight. In total, almost $2 trillion of market capitalization was wiped out from the stock market during the bust. As Warren Buffet famously remarked: “Only when the tide goes out do you learn who has been swimming naked”. And it soon became clear that nearly the whole industry had no pants on.

However, while the first phase of the internet/telecom cycle crashed, it laid the groundwork for some of the world’s most valuable companies today, such as Google, Amazon, and Facebook. These companies turned out to the be the major players of a new cycle two decades later - the AI cycle.

The “New” AI Cycle

Large language models are not new. The first GPT was launched in 2018, exactly one year after Google introduced the Transformer architecture. The broader field of AI has an even longer history, dating back to the 1950s when Alan Turing famously posed the Turing Test, a criterion for determining whether a machine can exhibit intelligent behavior indistinguishable from that of a human.

We define the “New” AI cycle as the period following the introduction of ChatGPT in November 2022. While there are many milestones that could mark this new era (such as ImageNet, AlphaGo, and Transformers), we believe ChatGPT represents the most seminal moment in modern AI, captivating the broader public's attention. Within just two months of its launch, ChatGPT surpassed 100 million users, far outpacing the adoption speed of any other technology application, including TikTok, YouTube, and Instagram.

In the nearly 18 months since ChatGPT's debut, the rate of innovation and progress has been nothing short of extraordinary. New foundational models are emerging almost daily, not just in text but also in multi-modal and the sciences. Autonomous AI beings, commonly referred to as “agents,” are now being developed to assist or even replace humans in various tasks, such as in sales and customer support. Even robotics, which had previously garnered less attention, is making a significant comeback. AI has undoubtedly reached a pivotal inflection point.

“We are at the iphone moment of AI” - Jensen Huang, CEO of Nvidia.

Comparing the Internet/Telecom Cycle to the Current AI Cycle

The Similarities

Both have similar ecosystem structures

During the internet/telecom cycle, infrastructure companies like Cisco and Nortel built the foundational backhaul and supplied the networking equipment. “Enablement” companies, such as telecom and browser companies, bridged the infrastructure and application layers. And application companies like Yahoo.com for search and Amazon for e-commerce created the use cases for consumers and businesses.

The new AI ecosystem is structured the same way:

Infrastructure: Nvidia’s chips are to AI what Cisco’s networking hardware was to the early internet. They provided the foundational backbone.

Enablers: Hyperscalers and LLM companies are to AI what teleco and browsers were to the internet. They enabled apps to be built on top.

Applications: AI-native companies like Writer, Perplexity and Glean are to AI what Yahoo/Amazon was to the internet. They created the apps to serve the end user.

Both cycles are occurring in the middle of an equity bull market

Both cycles are occurring amid prolonged bull markets. Despite events like Covid-19, the NASDAQ has appreciated almost tenfold in the past 15 years since the financial crisis. Similarly, the Nasdaq surged twentyfold in the 15 years leading up to the dot-com crash. Both bull runs have been fueled by a few common factors, such as favorable monetary policies, a relatively stable geopolitical environment, and financial market reforms.

Both technologies require significant investment on the infrastructure side

Both cycles required significant capital investments, particularly in infrastructure. The purpose is usually twofold: (1) to build out capacity to accommodate more users and (2) to improve the underlying technology.

For example, during the Internet/telecom companies, companies expanded network coverage to accommodate the growing number of internet users. At the same time, they invested in advanced technologies like fiber optics, which offered higher bandwidth than traditional copper wires.

Similarly, in the current AI cycle, companies are building new AI data centers to manage the increasing inference workloads demanded by users. At the same time, companies like OpenAI and Meta are continually training larger models. Some of the latest state-of-the-art models are now over a trillion parameters, and often require thousands of GPUs to train.

The magnitude of spending is likely to be similar as well. During the internet/telecom cycle, more than $500 billion (~$1 trillion in today’s dollars) was spent on the infrastructure buildout. A recent Goldman Sachs report estimates that the same amount will be spent in AI in the coming years, including significant investments in chips, data center and the power grid.

Both cycles drew significant VC interest, leading to high valuations

The current AI cycle, like the internet/telecom cycle, has attracted significant VC attention, leading to a surge in funding for startups. In Q1 2024, over $12 billion was invested in AI startups, doubling the previous year’s figures (excluding OpenAI’s $10 billion round). According to CB Insights, there are already more than 36 unicorns in the latest GenAI wave.

AI companies also enjoy valuations that are up to 60% higher than their non-AI counterparts, reminiscent of the internet/telecom cycle when hundreds of “.com” companies were funded at astronomical valuations.

Now that we have examined the similarities between the two cycles, let’s explore the differences.

The Differences

To explain the differences between these two cycles, we can use the same arguments cited in the similarities section above.

Both have similar ecosystem structures, BUT different revenue profiles

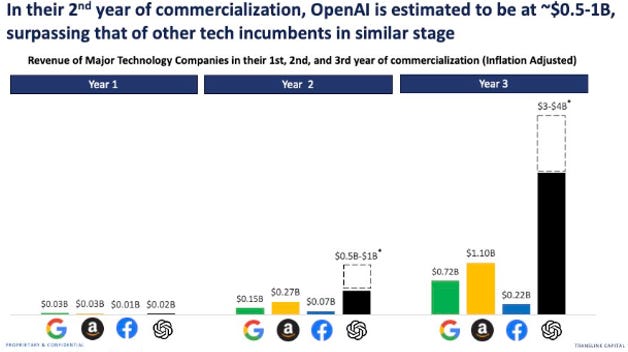

Although both technologies share similar ecosystem structures, the revenue profiles are vastly different. Even though we are still in the early phases, AI applications have already generated significantly higher revenue. We estimate that OpenAI alone is expected to generate $3-4 billion of revenue in only its third year of commercialization. This is more than the combined revenue of Google, Amazon, and Facebook in their respective third years. Other AI companies with notable revenue traction include Anthropic (~$200 million run rate), Writer ($100 million), Cohere ($35 million) Glean ($50 million+), Heygen ($20 million+), Perplexity ($20 million+) and more. Unlike the dot-com era where many internet application companies relied on non-financial metrics such as users, clicks, and eyeballs for funding, AI application companies are showing meaningful revenue streams much earlier on.

One major reason for the difference is the inherent nature of the technology. The internet is a network-based technology, where the value increases exponentially with the number of users. AI, on the other hand, can provide significant value even as a standalone technology. For example, I still receive a lot of value from ChatGPT even if I’m the only user. But if I was the only person on Earth using email, that wouldn’t be so useful. Because of the immediate applicability of AI, the path to monetization can be faster.

Both cycles are occurring in the middle of an equity bull market, BUT the economic environment differs

While both technology cycles happened amid bull markets, the overall economic environment are notably different. The second half of the 1990s in the US was characterized by exceptionally strong economic conditions. During this period, GDP growth rates consistently exceeded 4%, and unemployment rates fell to historic lows. Fed Chairman Alan Greenspan, popularly referred to as “the maestro” for his skillful handling of the economy over the previous two decades, fostered an environment marked by predictability and price stability. This created a risk-on environment for investors.

In contrast, the current economic conditions, while stable, are markedly different. The economy is still recovering from the impacts of COVID-19. GDP growth over the past few years has hovered around 2.5%, which is right around the US long-term average but far below the 4%+ growth experienced in the late 1990s. Persistent inflation due to monetary easing during 2020/2021 has limited the Federal Reserve's ability to lower interest rates, resulting in a slowdown in credit growth and a higher investment hurdle for investors. Consequently, investors are now in a more "risk-off" stance.

Another indicator of investor risk tolerance is fund flows. During the dot-com bubble, flows to equity increased by 76% at the peak in 2000. In contrast, equity fund flow has been negative in the past two years. This shift is leading investors to prioritize sustainable growth in the current AI cycle, moving away from the “growth-at-all-costs” speculative exuberance that characterized the internet/telecom cycle.

Both technologies require significant investment on the infrastructure side, BUT the sources of financing are different

While both technologies required substantial capital, the capital was acquired in very different ways. During the internet era, much of the capital came from the public markets and retail investors, with many companies going public earlier. For example, between 1996 and 2001, over 300 internet companies filed for IPO.

In contrast, it is more difficult to go public today as the threshold is much higher. As a result, most of the funding for AI companies is coming from the private market and big tech. Companies such as Microsoft, Google, Nvidia, and Salesforce are actively participating in many of the AI funding rounds. Even venture capital, traditionally the first in line to support new technologies, have stepped back at times, leaving big tech to lead larger rounds. The shift is partly due to VCs having less dry power compared to the previous cycle, but also because big tech companies have built large cash coffers that need to be reinvested back into growth. And what better way to invest in growth than to invest in AI right now.

Another key difference is that the telecom/internet cycle was financed by a significant amount of debt, both for investments and M&A. In contrast, today’s AI cycle is almost financed exclusively by equity (with the exception of some AI cloud providers that are starting to taking on debt). Hence, while the internet/telecom cycle coincided with a leveraging cycle, the AI cycle is happening in conjunction with a deleveraging cycle.

Both cycles drew significant VC interest, leading to high valuations, BUT AI business models are more sustainable and valuations are more reasonable

Both cycles attracted significant VC interest, but most internet startups during the dot-com era did not have sustainable business models. Take Priceline.com for example. The company sold excess ticket inventory from airlines. While the company achieved overnight success by selling more than 100,000 airline tickets in their first 7 month of business, they did this under an unsustainable unit economics, selling $35 million worth of air tickets which it had paid $37 million for. On top of the negative gross margin, the company burned upwards of $100 million on web development, marketing, and employee stock options. Despite its unsustainable business model, the company’s shares quadrupled on their first day of trading, ending with a market cap larger than United, Continental, and Northwest Airlines combined.

In contrast, while there are some examples of negative unit economics in the current wave of AI (For example, WSJ reported that Github Copilot was losing $20/month on each user), most companies are operating quite rationally. As an example, Anthropic was rumored to be operating at a gross margin of between 50-55% late last year. While this is lower than typical SaaS margins, the margins are at least positive and should improve with scale. With model token prices trending downwards for the foreseeable future, AI application companies should also see an improvement in margins, assuming prices hold up.

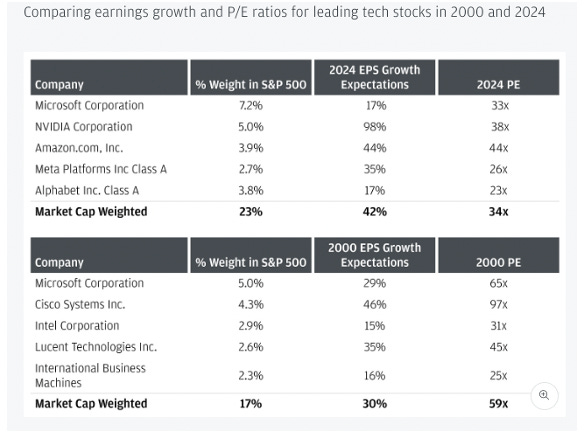

Additionally, public AI companies' valuations, while high, are still within reasonable ranges compared to their historical multiples. Even Nvidia, which has surged almost tenfold over the past 18 months, trades at a significant discount compared to its dot-com counterpart Cisco during the peak of the dot-com era.

So, after outlining the similarities and differences between the AI and internet/telecom cycle, we can now finally address our question:

Are we more or less likely to be in an AI bubble?

Are We Likely in an AI Bubble?

To answer this question, let’s systematically examine each comparison factor and evaluate whether it contributes to a greater or lesser likelihood.

Both have similar ecosystem structures, BUT different revenue profiles

LESS LIKELY: Because AI is less of a “network-based” technology than the internet, it has provided more immediate value to users. This means many AI application companies are already generating significant revenue with positive unit economics. While these economics aren’t at ideal levels today, they should theoretically improve with scale as fixed infrastructure costs are spread over a larger user base. While we don’t expect the majority of these companies to be cash flow positive or self-sustainable anytime soon, they should continue to receive funding as long as they’re growing and the ROI remains attractive. This mitigates the risk of a mass exodus of unsustainable companies that we experienced during the dot-com crash.

Both cycles are occurring in the middle of an equity bull market, BUT the economic environment differs

LESS LIKELY: Although equity markets are performing well today, investors are in a much more “risk-off” mindset compared to the dot-com era. The underlying economy, including GDP growth, inflation and unemployment are all worse off than the late 90s. The fragile economic environment combined with the cautious investment environment should help prevent the excesses seen during the dot-com boom. Douglas O’Laughlin from Fabricated Knowledge put it well when he said: “The entire AI build-up so far has happened during a rate hike cycle. Nvidia’s revenue has gone parabolic during a Fed hiking cycle. This doesn’t mean that this cannot be an overbuild, but it helps prevent probably the worst of speculative tendencies”.

Another example of this is the interest rate that credit providers are charging to specialized cloud providers like Coreweave. We’ve heard that these rates are in the high-single to low-double digits - this shows that credit investors are still prudently maintaining a high hurdle rate and are risk-aware.

Both technologies require significant investment on the infrastructure side, BUT the sources of financing are different

NEUTRAL: Today’s AI financing primarily comes from VCs and big tech, unlike the internet/telecom cycle, which was funded largely by public institutional investors and retail. This difference likely mitigates the likelihood/risk of being in a bubble for several reasons:

History shows us that bubbles typically start taking off when the general public gets heavily involved. Currently, the public market has a limited number of AI-native companies available for investment. And while the few that do exist (e.g., Nvidia) have appreciated considerably, the valuation remains grounded in near-term earnings.

Unlike public markets where price discovery is in real-time, private markets are marked-to-market infrequently. This reduces the risk of both bubble buildup and the panic sell-off when a bubble inevitably implodes.

Even if some investments fail, big tech companies have strong cores businesses and operating cash flow to absorb investment write-offs without significant impact and contagion to the broader market/economy.

Furthermore, the reliance on equity rather than debt financing keeps leverage low and helps to prevent bubbles from inflating.

The counterargument here is that because big tech is so cash-rich today, and view AI as such a strategic priority, they may be less sensitive to valuations. The ongoing battle between companies like Meta, Google and Microsoft could push valuations to unreasonable levels, potentially contributing to a bubble. For example, in the latest Meta earning call, Zuckerburg announced he was planning to increase CapEx by several billion dollars to support the company’s AI roadmap. The arms race for GPUs and other AI infrastructure will likely continue to persist, leading to higher valuations for everyone.

Both cycles drew significant VC interest, leading to high valuations, BUT business models today are more sustainable and valuations are more reasonable

LESS LIKELY: While valuations of public AI companies have picked up since Covid-19, they remain reasonable relative to the dot-com era.

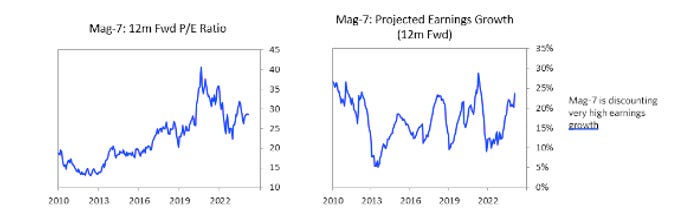

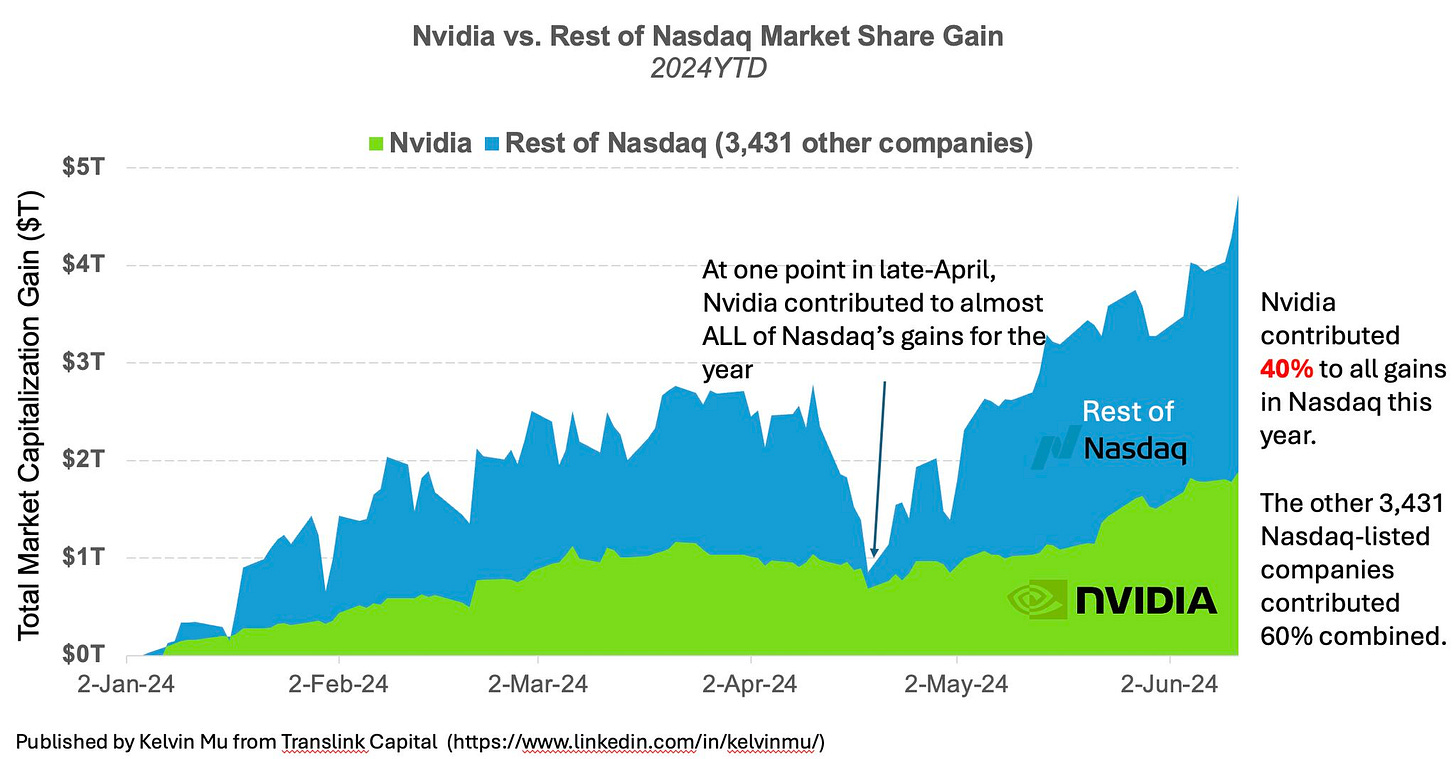

It’s true that the “magnificent 7” (e.g., Alphabet, Amazon, Apple, Meta, Microsoft, NVIDIA, Tesla) has driven the meaningful share of gains in the US equities over the past year and now account for 25% of the S&P500 market cap. Nvidia is particularly noteworthy as its gains have accounted for almost half of the combined gains of the other ~3,400 companies in the NASDAQ. Yet, despite these recent gains, the forward price-earnings ratio of the mag-7 still looks quite reasonable.

Is This Déjà Vu? We Don’t Think So – At Least Not Yet.

Based on this analysis, it is unlikely we are in a bubble right now. This is not to say a bubble will never occur, just that this still looks and feels quite different from dot-com.

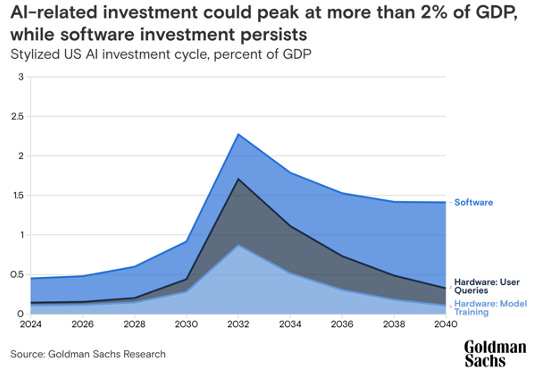

We estimate that the total investment in this current AI cycle is somewhere in the range of $100-$200 billion, still far below the ~$1 trillion (in today’s dollars) that was spent during the internet/telecom cycle. Others believe that spending could be even higher - a recent survey by Goldman Sachs puts the spending as high as 2.5% of US GDP - roughly $500 billion/year at today’s GDP.

One reason this number isn’t even higher is because there is still a significant bottleneck on the hardware side (though this is improving). Without this bottleneck, overall spending and investment might be higher, increasing bubble concerns. However, from the telecom cycle, we know it took almost a decade for spending to peak. Keeping in mind that it’s been only 18 months since the “iphone moment of AI”, we believe the AI cycle is still in the first or second inning.

What Can we Learn from the Dot-com Bubble?

Regardless of whether you believe in the AI bubble or not, there are important lessons that we can take from the dot-com bubble:

Infrastructure buildouts takes time – Foundational technologies often require a long time to reach peak buildout. The internet/telecom cycle took almost a decade to reach peak buildout, and other technologies such as the railroad took even longer (~50 years). The AI infrastructure cycle shouldn’t be any different. In fact, because of the current bottlenecks in chips, this cycle may be prolonged further.

First-mover advantage can be a disadvantage – Before there was Google, there was Archie, Veronica, Jughead, the World Web Wanderer, Aliweb, Excite, Galaxy, Dmoz, LookSmart, WebCrawler, Lycos, Infoseek, Inktomi, Ask Jeeves, alltheweb and Altavista, to name just a few. This happened not only in search, but also in e-commerce, social media, and mobile. It usually takes a while for people to learn how to leverage the power of new technologies, and the gap between first movers and subsequent followers usually narrows in the early phases of a technology. More often than not, the first winners may not be the ultimate winners.

Winner-takes-all dynamics - Like in internet/telecom, AI is likely to follow a winner-takes-all dynamic. In the internet/telecom cycle, a few companies – Microsoft, Amazon, Google, and Facebook – took most of the economic pie. The AI cycle is likely to be the same because both technologies rely on the self-reinforcing power of data network effects. For investors, the ability to pick these few winners can often make the difference between rags and riches.

M&A consolidation will likely happen towards the end of the cycle - In the telecom/internet era, most M&A transactions happened in the second part of the decade. In 1999 alone, there was over a trillion dollars’ worth of M&A transactions. Typically, consolidation happens when the economics become more mature and the winners are largely determined already. We aren’t seeing much consolidation in the AI space today - this is another indicator that we’re early into the cycle.

Boom to bust can happen very quickly - In the internet era, 80% of wealth was wiped out in a period of less than three years. History shows that sharp reversals in confidence can happen abruptly, often with little advance notice.

Beyond just the technology – Other factors such as the macroeconomy, regulatory environment, and geopolitics, are equally as important. Current discussions around “AI sovereign” are reminiscent of the internet/telecom era and explain the emergence of regional winners in that cycle (Deutsche Telekom in Germany, NTT in Japan, SK Telecom in Korea, etc.). New challenges like copyright issues and the proliferation of deepfakes, which were not relevant previously, have now become critical topics.

Concluding Remarks

Sequoia recently published an article titled: “AI’s $600B Question”. The article argued that we needed ~$600B in application-side revenue to justify the current level of infrastructure spending and that we're far from reaching that figure today. While the article was insightful and made a good point, one challenge with this analysis is estimating the internal efficiency gains not directly captured by revenue. For example, consider the use case of Meta adding an “Ask Meta” search bar on all Facebook/Instagram. Or Klarna replacing their 600 customers agents with AI. Both are examples of AI providing significant value, yet the value is not being captured in revenue alone. Instead of focusing on $600B in revenue, we should focus on $600B in value creation. To put this into perspective, $600B is just 0.6% of world GDP. With firms like JP Morgan, Goldman and McKinsey projecting that generative AI could increase GDP by 7-10% in the not-so-distant future, there’s an argument to be made the AI is just getting started.

But history also shows us that when it comes to foundational technologies, there likely will be overinvestment. The internet/telecom boom resulted in more than 80 million of fiber being laid. Within a few years, the cost of bandwidth fell by more than 90 percent and by 2005, almost 85% of broadband capacity was still unused. Similarly, during the railroad buildout of the 19th century, over a quarter-million miles of tracks were laid, most of which were underutilized.

Yet, the cheap bandwidth enabled the next wave of internet companies like Google, Facebook and Netflix to thrive. Similarly, the excess railway capacity led to cheaper transportation costs, enabling companies to grow their customer bases and expand operations. Where there were some losers in the cycle, society as a whole benefited immeasurably.

AI will be no different. The power of AI will transform every facet of our society, from the micro changes in our day-to-day lives to the macro changes in global geopolitics. It will challenge our values and assumptions and make us reconsider what it means to be human. It is inevitable that some capital will be wasted getting there. We may even experience a bubble or two. But this is part of the growing pains of advancing humankind. Society, like our individual lives, seldom take the shortest route. As to the argument that we are in a bubble right now, we think it deserves some reconsidering.

Afterword:

Regular readers of my content know that I typically stick to shorter pieces. This is my first foray into writing something much lengthier. Thank you for taking the time to read all the way through. I value everyone’s time, which is why this piece took me a month of careful writing to put together.

If you have any feedback on how I can improve for next time, I would love to hear it. If there are any other topics you would like me to write about, please comment below. As always, feel free to reach out if you want to chat. I can be reached at kmu@translinkcapital.com.

Until next time,

Kelvin

Sources used (in alphabetical order):

A Short History of Financial Euphoria, by John Kenneth Galbraith

Bank of America, Global Fund Manager Survey, published March 2024

https://business.time.com/2007/07/10/citigroups_chuck_prince_wants/

https://www.cbinsights.com/research/ai-startup-valuations/v

https://www.cbinsights.com/research/generative-ai-funding-top-startups-investors-2023/

https://www.cnbc.com/2024/02/26/jpmorgan-ceo-jamie-dimon-says-ai-is-not-just-hype-this-is-real.html

https://www.demandsage.com/chatgpt-statistics/

https://news.crunchbase.com/ai/robotics-venture-funding-strong-q1-2024/

Engine that Move Markets, Technology investing from Railroads to the Internet and Beyond, by Alasdair Nairn

https://ethernetalliance.org/wp-content/uploads/2022/03/EthernetRoadmap-2022-Side1-Final-PRINT.pdf

Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis and U.S. Office of Management and Budget (FRED),

https://fred.stlouisfed.org/

https://iot-analytics.com/what-ceos-talked-about-in-q1-2024/

https://www.jpmorgan.com/insights/investing/investment-trends/how-to-invest-in-ais-next-phase

https://www.linkedin.com/pulse/we-stock-market-bubble-ray-dalio-zpdre/

The Man who Knew, the life and times of Alan Greenspan, by Sebastian Mallaby

https://money.cnn.com/2000/11/09/technology/overview/

https://www.nytimes.com/2024/04/24/technology/meta-profit-stock-ai.html

https://www.sec.gov/search-filings

https://www.sequoiacap.com/article/ais-600b-question/

https://www.visualcapitalist.com/sp/3-reasons-why-ai-enthusiasm-differs-from-the-dot-com-bubble/

https://www.wsj.com/tech/ai/ais-costly-buildup-could-make-early-products-a-hard-sell-bdd29b9f

Great analysis! Delving into the depreciation problem focused on in the Sequoia article would be beneficial (https://www.sequoiacap.com/article/ais-600b-question/). Seems like the base layers will depreciate fastest, and lead to margin compression, even while apps and marketplaces and related ecosystems will grow in impact/valuation. Also, you need to fix your link for the Dalio analysis: https://www.linkedin.com/pulse/we-stock-market-bubble-ray-dalio-zpdre/

I personally think we are in a bubble simply for the fact that current AI systems literally take no account for the experience of the human operator, always just focusing on new features, faster generation, things like that. At some point, we as humans just grow weary of its use, and then we experience fatigue with the technology, and following we simply start to ignore it. We have seen this time and time again.

People are starting to experience AI Fatigue as a legitimate phenomenon. As someone who is starting to experience it myself (I don’t want AI in my washing machine thank you very much) I have found a few case studies into researching my own conditions into it.

AI Fatigue: A Study into the Impact of Artificial Intelligence on Employee Fatigue

https://www.amazon.com//dp/B0D2BQV1DC

there are a couple others too, but just my two cents.